The History and Significance of Hanukkah: A Deep Dive into the Festival of Lights

Understanding the Time Between the Testaments

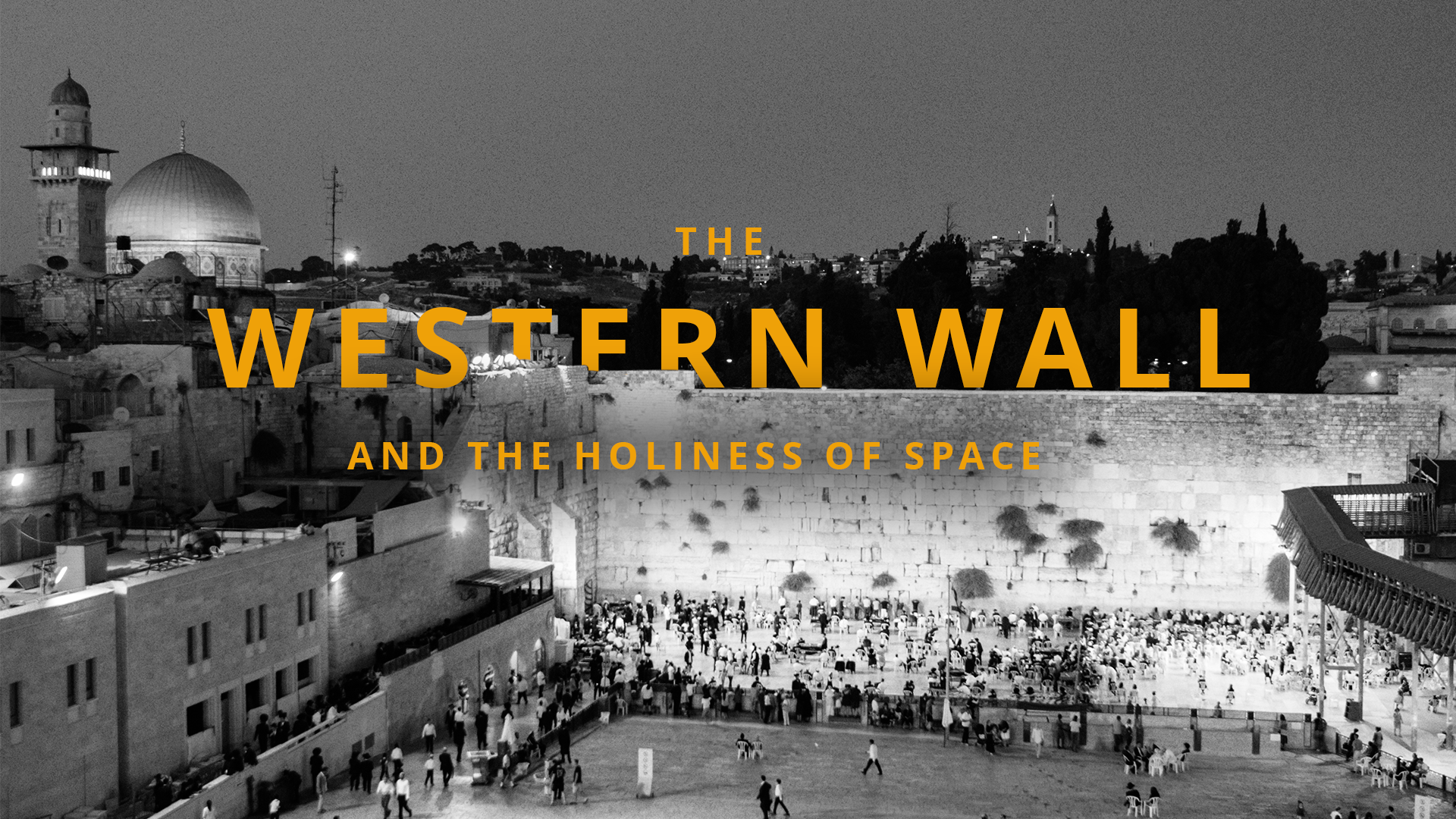

The 8-day Jewish holiday of Hanukkah (also spelled Chanukah) is known as the “Festival of Lights.” At the heart of its celebration is the nightly lighting of the menorah. This tradition commemorates the miraculous multiplication of the sacred oil during the Maccabees’ re-dedication of the Temple in Jerusalem (learn more about this fascinating and inspiring story here). Let’s take a deeper dive into the time leading up to and surrounding that first Hanukkah. What does that era have to do with the texts known as The Apocrypha? What contributed to the rise of “apocalyptic” literature and its effect on Jewish culture? Join us as we prepare to celebrate Hanukkah and the arrival of the Light of the World!

For most Christians, the Old Testament concludes with the Book of Malachi and resumes with Matthew’s Gospel, resulting in a 400-year gap (approximately). Some see this as an intermission of sorts, where in the theater, the crew sets the stage behind the curtain and out of view for the next act. In this understanding, it’s as if God took a break from dealing with humanity for several centuries to set the stage for the Messiah and, by extension, the Apostles. Some have described this period as “The Four Hundred Years of Silence.”

Frankly, this “time between the Testaments” is a somewhat murky part of world history (and Jewish history specifically) that students often overlook. This omission often causes us to miss the majesty of what God was doing with and through His people during the era.

Let’s first clarify a couple of common misconceptions. First, many presume that the only prophets are those who have biblical books named after them (or at least their prophecy recorded). This thought does not hold up as we scrutinize Scripture, which mentions thousands of prophets in passing. Consider 2 Kings 2:7, “Then 50 of the sons of the prophets went and stood aside at a distance from them, while the two of them stood by the Jordan.” We find another notable example you will surely recognize in the story of Jesus’ birth. “Now Anna, a daughter of Phanuel of the tribe of Asher, was a prophetess. She was well advanced in age, having lived with a husband only seven years and then as a widow until age eighty-four. She never left the Temple, serving night and day with fasting and prayers” (Luke 2:36). There is no “Book of Anna,” but she absolutely was a prophet.

The second major misconception is that if Scripture doesn’t describe God as active, He must have been, by default, inactive. This presumption overlooks the theological truth: “the Keeper of Israel neither slumbers nor sleeps” (Psalm 121:4). Reality unfolds within the context of His sovereign rule. God’s apparent inertia is almost always a misinterpretation of events. Just because we don’t see God working doesn’t mean He isn’t. His stillness may be a strategic delay: “But when the fullness of time came, God sent out His Son, born of a woman and born under the law” (Galatians 4:4).

During this Intertestamental Period, we see the rise and fall of empires required to bring about Roman control over Jerusalem so that the Messiah could be born on a particular day and then also die by crucifixion on a specific day, all under Roman authority. Beyond this, developments were needed in religious experience and philosophy to prepare not only the Jewish world but also the Gentile world for the advent of the Messiah and acceptance of the Gospel. Any serious consideration of aligning all these substantive details quickly becomes a mind-bending affair. God was active between Malachi and Matthew, even if He did not inspire any writers to record an account of it.

However, a collection of works crafted during this era tells the story of God’s interaction with Israel—The Apocrypha. These intertestamental works continued to tell the story of God’s interaction with Israel. Historically, Jews and Christians both saw the Apocrypha as having merit, though not considered “canonical” (i.e., divinely-inspired text). Certain texts from this period even appear in the New Testament! We read a quote from 1 Enoch in Jude 1:14, “It was also about these people that Enoch, the seventh generation from Adam, prophesied, saying, ‘Behold, the Lord came with myriads of His kedoshim, to execute judgment against all. He will convict all the ungodly for all the ungodly deeds that they have done in an ungodly way and for all of the harsh things ungodly sinners have spoken against Him.’”[i]

[i] While 1 Enoch is not part of The Apocrypha, this collection of traditions and writings was probably composed contemporaneously (between the 4th century BCE and the turn of the era).

Though the Jewish people had returned to their land from Babylon, they still saw themselves in exile for various reasons. They had a rebuilt Temple, but it was a disappointment to any who remembered the original, “But many of the kohanim, Levites and patriarchal leaders, older men who had seen the former House, wept loudly at the sight of the founding of this House” (Ezra 3:12). They remained a vassal state subject to the Persian Empire. Then came the invasion by Alexander the Great, whose death gave way to the Seleucid Empire (312–64 BCE). The prophecies in Daniel 7-12 accurately predict Antiochus’ defeat at the hands of the Ptolemies and Rome and his turning his wrath upon Judah.

That series of events would result in the Maccabean Revolt, recorded in the books of the Maccabees and Judith. In this uprising, the Jewish people fought a campaign of guerilla warfare and political assassination as they struggled for their very survival. Simmering in the collective Jewish consciousness were the prophetic promises from as far back as Amos (see chapter 9), Jeremiah(see chapter 33), and the others, which predicted a restored Davidic Kingdom with pure Temple worship.

It is hard to imagine the intense betrayal felt by those who fought for that restoration when the victorious Maccabean leaders, Tzadokite priests (from which the term Sadducee comes), assumed the throne and combined the kingship and priesthood. For the first time in hundreds of years, the Judean kingdom was genuinely independent, but instead of seeing the prophecies fulfilled, the opposite came to pass. They had an inferior Temple administered by renegade priests.

Then, to make matters worse, Rome conquered them, and Pompey the Great (106-48 BCE) carried off what little temple artifacts they did have. Under the crushing occupation of Rome, a new type of literature arose; it was called “apocalyptic.” “Speaking generally, the prophets foretold the future that should arise out of the present, while the apocalypticists foretold the future that should break into the present…Other features of the apocalyptic outlook include the willingness to abandon the historical process in favor of the all-important consummation, an interest in consoling the righteous rather than rebuking them for their failures, and the conviction that they were living in the last days. Apocalyptic is also characterized by a rigid determinism in which everything moves forward as divinely preordained according to a definite time schedule and toward a predetermined end. While this led to a rather complete pessimism about people’s ability to combat the evils they encountered, it nevertheless bred confidence that God would emerge victorious even in the apocalyptist’s own lifetime.”[i]

[i] Robert H. Mounce, The Book of Revelation (Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1998), 3-4.

Apocalyptic literature from that period includes Jubilees, 2 Esdras, 2 Baruch, Apocalypse of Abraham, the War Scroll (1QM), and the Dead Sea Enoch fragments. All paint a picture of a people who saw themselves in an epic showdown between light and dark, good and evil. They present suffering as the order of the day and the patient anticipation of the victory that would come with the Messiah.

With this level of deep, pervasive longing for messianic deliverance, it should be of no surprise to us that Jewish sages would travel from the East to honor the Lord’s birth, “Now after Yeshua was born in Bethlehem of Judea, in the days of King Herod, magi from the east came to Jerusalem, saying, ‘Where is the One who has been born King of the Jews? For we saw His star in the east and have come to worship Him’” (Matthew 2:1). Two thousand years on, as we patiently wait, wise men still seek him. “Amen! Come, Lord Yeshua!” (Revelation 22:20)