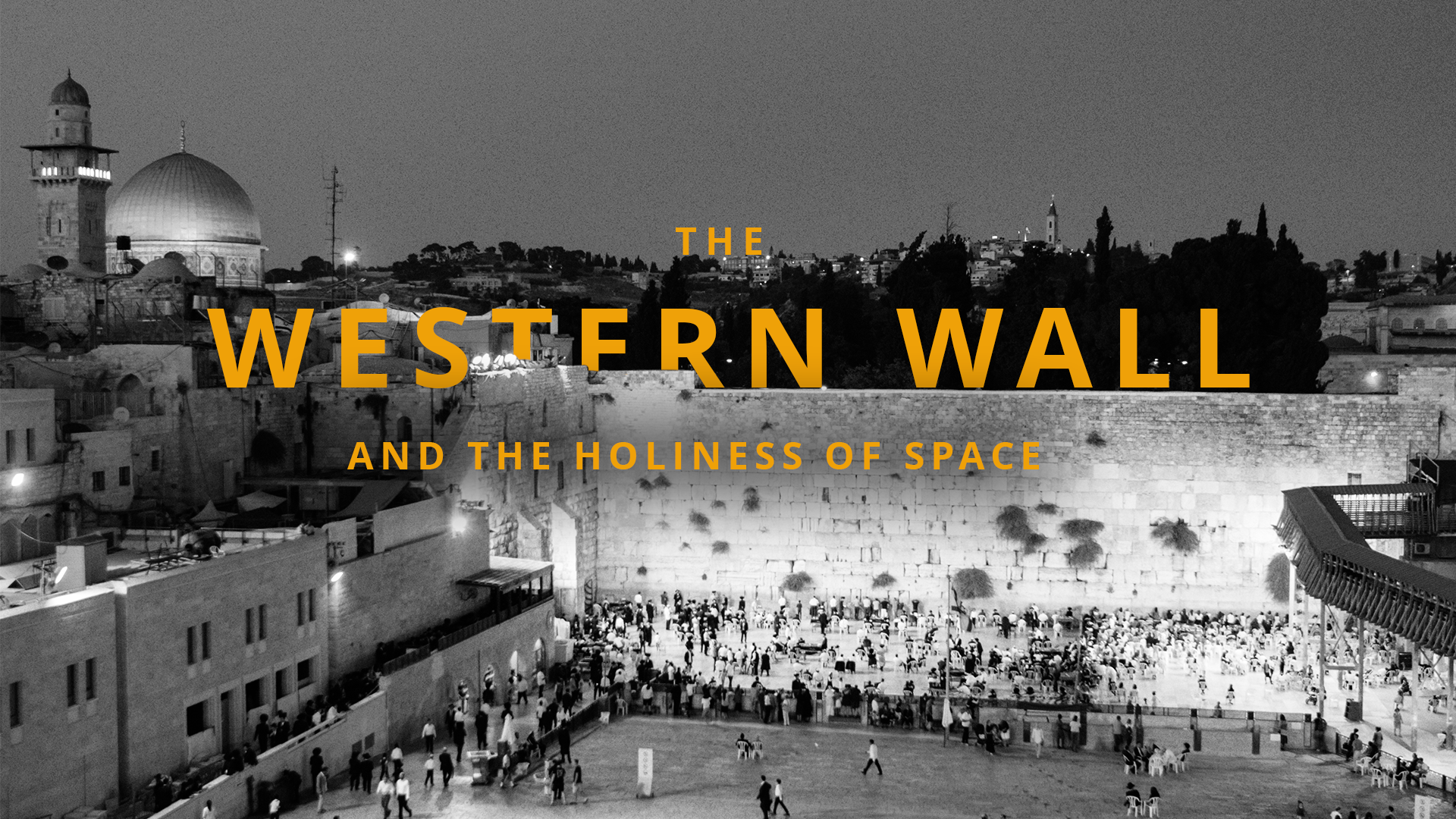

The Western Wall, or “Wailing Wall,” is one of the most well-known and beloved holy sites in all of Israel. True aficionados may refer to it as the Kotel. Most people have at least some vague awareness of it. Presidents, Prime Ministers, and Popes have made very public visits to the site throughout the years. You may have even stepped foot there on a tour at some point. Despite all of this, many people often remain unaware of its history or significance.

Arguably, the most common misconception about the Western Wall is that it was once part of the actual Temple. Solomon’s Temple, rebuilt by Zerubbabel in 516 BCE, was a relatively small affair that sat precariously atop a mountain peak known as Mount Moriah. It was small, and it wasn’t very pilgrim-friendly. That state of affairs continued until the reign of Herod I (also known as Herod the Great). Herod was not very popular, so to appease his Jewish subjects, he expanded the Temple site drastically. To accomplish that, he built a massive retaining wall around the peak of Mount Moriah. He then backfilled it to create a 40-acre plaza capable of accommodating massive crowds (some sources suggest upwards of one million people).

Though the Romans destroyed the Temple in 70 CE, the retaining wall remained largely intact. It wasn’t for lack of trying, though. On the western side of the complex, the area closest to the Holy of Holies, the Romans attempted to demolish the retaining wall. Then they hit the “Western Stone”—a massive stone that weighed an incredible 558 tons. After trying to chip away at it, they gave up. Instead, the marauders came up with other ways to desecrate the Temple Mount and much of the surrounding areas.

During the Mamluk period following the Crusades, the hilltops of Mount Zion and Golgotha became the preferred locations for the wealthy, who built a series of arches spanning the valley between those western hilltops and the Temple Mount. It is upon these arches that current Jewish, Christian, and Arab quarters (i.e., areas of the Old City of Jerusalem) are situated. In all of that building, two sections of the western stretch of Herod’s retaining wall remained exposed.

The western side of the retaining wall runs just over 1,600 feet. The Kotel (Western Wall) is a 187-foot section of it that is designated for prayer. The Kotel HaKatan (the “Little Western Wall”) is sixty feet long. Holy Land tours rarely include a stop at the Kotel HaKatan due to its location in the Arab quarter. It does have historical significance though. Due to Christian and later Muslim objections to Jews praying on top of the Temple Mount—not to mention Jewish religious opinions regarding ascending the Temple Mount—the closest Jews could come to praying there were the sections of the wall that were available. These walls on the western side were the closest to the site of the Holy of Holies.

Historically, there were three places of prayer: the Kotel, the Kotel HaKatan, and a synagogue located in the arch system under the Arab quarter. It was destroyed and rebuilt several times (there are four there now, one open to the public and three that are invitation only).

Historically, these sacred areas were “technically” available for prayer, but even with that limited access, they were far from safe. Rabbi Yedidia Raphael Chai Abulafia (1800-1869), at the time chief Rabbi of Jerusalem, wrote that if a person was in desperate need, they should go pray at the Kotel forty days in a row. God would answer their prayer because of the great Mesirat Nefesh (giving over of the soul/self-sacrifice) because of the great danger of going to the site daily. Considering the funeral procession for his father—which went from Jerusalem to the Mount of Olives—was attacked, he had some experience with said dangers. In general, pogroms (i.e., organized mass violence) against Jews were a common occurrence in Judea, and this only gained in frequency until the birth of the State of Israel in 1948.

[i] We should note that the Kotel (like the Kotel HaKatan today) was not always the expansive, welcoming plaza it is currently. Years ago, it was more of a wide alley.

[i] https://www.fondapol.org/en/study/pogroms-in-palestine-before-the-creation-of-the-state-of-israel-1830-1948/

As a result of the Six-Day War in 1967, the State of Israel regained control of the “Old City” of Jerusalem, and the Temple Mount specifically. Of course, many—Jews and Christians alike—interpreted this development as a supernatural liberation, a manifestation of God’s sovereignty. A few days after the war, more than 200,000 Jews flocked to the Western Wall in the first mass Jewish pilgrimage to this location since the Romans destroyed the Temple in 70 CE. This historic period transformed the Kotel into the freely accessed place of prayer that it is today.

Some will then undoubtedly wonder why it was such a vital thing to pray there, especially if it was potentially (or actually) dangerous to do so. King Solomon’s prayer at the dedication of the Temple is key to understanding the continuing value of the site: “Now my God, I pray, let Your eyes be open, and let Your ears be attentive to the prayer made in this place” (2 Chronicles 6:40). This biblical source (cf. all of chapters 6-7), an extensive discussion in the Mishnah Berakhot (ch. 4), and the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds’ explication of the site’s profound meaning, reveal its spiritual significance. Ideally, one would pray on the Temple Mount directly, but since that isn’t currently possible, the next best option is to get as close as possible to the Holy of Holies—the Western Wall.

One may notice people slipping little pieces of paper with prayers written on them into the wall. That is a custom that started in the 1800s. Its exact origin is unknown, but the devout generally see this as a tangible way to pray, similar to Hezekiah, who laid Sennacherib’s letter before the Lord (cf. 2 Kings 19:14-19). The rationale is that as we place these things before the Lord, or as close as we can get to His abode, we express our trust in Him.

According to numerous Jewish sources, the Tabernacle and the Temple modeled God’s throne room in heaven, and in a sense, they overlap.[i] Hence, all the weavings and (later) carvings of seraphim and cherubim as decor. Likewise, in the Book of Revelation, we have a description of the throne (cf. Revelation 4:2-3), which corresponds to the ark of the covenant, the bowls of incense, which are the prayers of the saints (cf. Revelation 5:8), and the altar where those prayers get offered (cf. Revelation 8:3-4). These details are relevant because in Jewish thought, as described in the earlier-mentioned sources, although the physical structure of the Temple may currently be absent, its spiritual counterpart remains.

Not unlike the woman who pushed through the crowd to touch the hem of Yeshua’s garment (cf. Mark 5:25-34) or Zacchaeus who climbed a tree to get a look at Jesus (cf. Luke 19:1-10), praying at the Kotel gives the Jewish people that sense of pressing through to get as close as possible to the place of His throne.

[i] Exodus 25:9;40; 1Chron 28:11-19; Talmud Chagigah 12b, Ta’nit 5a, Sukkah 41a